Vietnam, Cambodia, Covid-19 and America

Tin soldiers and Nixon coming

We’re finally on our own

This summer I hear the drumming

Four dead in Ohio

Fifty years ago, April 29th, President Richard Nixon launched the final large-scale American offensive of the Vietnam War, the incursion into Cambodia. The attack caught just about everyone by surprise: the Cambodians, North Vietnamese, and the American and world public. Tactically, it produced some positive effects and bought South Vietnam some time to prepare to defend itself as the US drawdown continued rapidly afterward. Strategically, it was a massive failure on both the world stage and within the US.

One effect was a resurgence of anti-war protests in US towns and cities and on college campuses. Most notoriously, US Army National Guard troops opened fire on protesters and innocent students alike, leaving four young people dead at Kent State University on May 4, 1970. The lyrics of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young evoke the turbulent mood of horror, outrage, and shock. Young watched coverage of the shooting, wrote the lyrics and the group recorded it on May 21st. The B side of Ohio was Stephen Stills’ ode to the war dead, Find the Cost of Freedom.

Find the cost of freedom

Buried in the ground

Mother Earth will swallow you

Lay your body down

The cost of freedom refers to the death of all those fighting for it, the anti-war students in Kent as well as the soldiers in Vietnam.

As she did fifty years ago, Mother Earth continues to make room for those dying in the current “war” against the Covid-19 virus — no matter the age, sex, race, or religion.

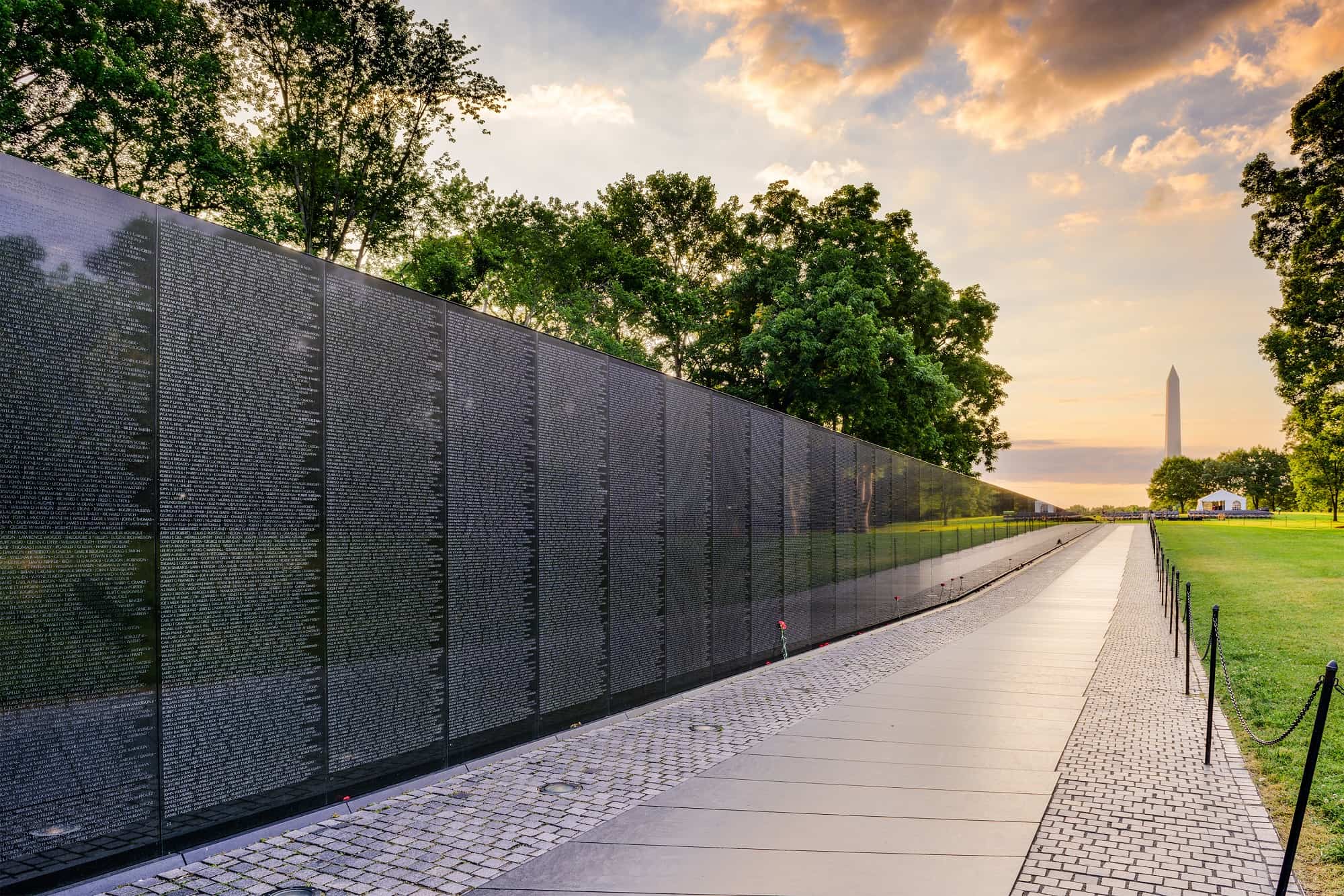

On April 29th, the numbers of Americans felled by Covid-19 surpassed all those American lives lost in Vietnam over a period of almost two decades. As I write this, we have lost 55,356 these past two months and more every day. In the entirety of the Vietnam War we lost 58,193.

In the war, most of the dead were young men. Some 40,000 were 22 or younger, and 3,121 were 18 or younger.

The youngest name on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial wall in Washington DC is that of Dan Bullock of North Carolina by way of Brooklyn. He altered his birth certificate in 1968 to join the US Marines after watching the Tet Offensive on television. He survived Parris Island boot camp and went to Vietnam, where he was killed in 1969. The African-American private and Marine rifleman was 15 years old.

Today, most of those dying of Covid-19 in the US are older than the mean. Some 62 percent are 65 and older. Only 5 percent are under age 44. However, young people and even babies have died from it.

The oldest American to perish thus far is Philip Kahn, who served as a sergeant in the US Army Air Forces in WWII. He was 100 years old. His twin brother, Samuel, had passed from the Spanish Flu weeks after his birth a century ago.

The oldest American to die in Vietnam was 62. Only 125 of those killed were 50 or older. War is fought by the young. The battle against Covid-19 knows no such rules. All are vulnerable.

In Vietnam, eight American women gave their lives. In the Covid-19 fight, women make up 38 percent of the US deaths thus far.

In Vietnam, Philadelphia’s Thomas Edison High School lost 54 of its graduates. Philadelphia had suffered terribly in the 1918-1919 Spanish Flu epidemic and is, again today, struggling against Covid-19.

In fact, the states that suffered the most casualties in Vietnam are some of those with the highest rates of deaths today against Covid-19. New York trailed only California in the most deaths in the war. Other states in the top six included Pennsylvania, Ohio and Michigan along with Texas.

The most American deaths in a single day in Vietnam was 245 on January 31, 1968, in the first days of the Tet Offensive. With 2,415, May 1968 saw the most deaths in a month, during Tet’s second phase.

Meanwhile, the Covid-19 virus is taking American lives at a rate of over 2,000 per day.

While every death is a tragedy of some magnitude, some affect us more for various reasons. One is timing. On their first day of combat duty in Vietnam, 997 Americans lost their lives. And on what was supposed to be their final day after a year of combat duty, 1,448 gave the supreme sacrifice.

Today, we are seeing grandparents and parents unable to be seen or held in their last moments, spouses dying alone, babies succumbing soon after their lives had begun.

Fifty years ago, American society was struggling with a great many issues. Race, gender/women’s liberation, drugs, the environment, entitlements and more. President Lyndon Johnson had begun the focus of the Great Society programs after he visited poor whites in Appalachia in 1964. The appalling conditions he found there – lack of education, healthcare, employment, stable family structure and more – is what engendered his massive government response, a response that went well beyond Appalachia to the wider country in a war on poverty.

Today, once again, poor whites across America (especially in rural areas that have not garnered jobs from the revolution in global networking) are finding themselves in the situation LBJ saw in 1964. We are seeing what are called deaths of despair, as thousands of our brothers and sisters kill themselves with alcohol, heroin, meth, and opioids in an epidemic that yearly rivals the total deaths in Vietnam.

America also faced a crisis in 1970 as it looked toward its federal government. At the beginning of the conflict, the public and the media were initially supportive of the reasons for going to war. And, in general, they were also supportive of the tactics, operations and strategies employed by the military and civilian leadership in Saigon and DC.

However, when the public saw that lies had been and were being propagated to continue the war, the public rebelled. For instance, LBJ and his chief military commander in Vietnam, William Westmorland, led the public to believe the war was almost won in the last days of 1967. Then, when the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong launched a huge, nation-wide offensive across all of South Vietnam a month later, even entering the US Embassy compound, the American people lost faith with the program. North Vietnam’s Tet offensive, probably a tactical defeat, became, more importantly, a strategic success. LBJ lost heart and decided against running for a second term.

Richard Nixon took advantage of a divided Democratic party to become president in January 1969 with a promise to end the war with honor and bring American boys home. Thus, his offensive into Cambodia in April 1970 caught everyone by surprise. It seemed one more, great big lie had been foisted on the American people.

The drumbeat of falsehood, from the Gulf of Tonkin incident through Tet to Cambodia and then fully exposed with the publication of The Pentagon Papers in June 1971, led to a collapse of faith by the American people in its leaders.

The revelations of Nixon’s coverup of the Watergate break-in finally led to an almost complete break of trust after a decade-long lack of forthright federal leadership in the racial conflicts of 1965-69, and the prosecution of the Vietnam War. America — left-right, black-white, young-old, poor-wealthy – was fed-up and demoralized.

It was a long road back. And on the way back, much of the evils of those days were papered over and never fully resolved or realized. So that they remained, below the surface, ready to fester again.

Today, when the Covid-19 virus hit and the federal government began taking actions such as closing the borders and issuing initial guidance on aspects such as social distancing, the American public initially rallied around its leaders and was prepared to support the required actions deemed necessary.

However, amidst half-truths and outright lies, and mixed messages on everything from closing and reopening to treatments and equipment, the lack of a federally coordinated response resulted in a public unaware of who was calling the shots. And when it became apparent that this flawed federal response was incapable of meeting the immediate needs in many areas, the people and press began to question their leaders. Primed perhaps by the experiences of the Vietnam era, and exacerbated by the anti-government messaging of Ronald Reagan and others, the public has a much shorter leash on its tolerance for lies and ineptitude. A crisis of confidence is again ensuing.

Many of the issues facing America in 1970 – race, gender, entitlements, immigration, environment – are the same facing America today. We had reached a sort of nadir, a rock-bottom, after Vietnam and Watergate. But we gradually pulled together and set out once again to make America a better place.

That is where we are now. This is a trying time. It is, indeed, a war. The enemy is real, if difficult at times to grapple. It morphs and we must adapt to its changes. We can do this. We will do this.

Today the battle is not being waged halfway around the globe. It is in our towns and hospitals. It stalks our neighborhoods and businesses. It is in our densest cities and in our rural hamlets coast-to-coast. This is a fight on our home turf. Beyond the struggles for civil rights, we have not waged a battle of this magnitude on our shores since our Civil War 160 years ago. The country had not been set against itself as in that conflict till Vietnam. Today we are at an inflection point once more. Surely now is a time to gather together our communal strength when our hearts, in Abraham Lincoln’s words, are “again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

Americans have met every challenge set before them for a quarter millennium. We see opportunities in them. Opportunities to do better, to build stronger. America is a promise. Our Declaration sets out our ideals. Who we are and why we are here. All men are created equal. We have not yet fulfilled our promise, achieved our greatness. It is always somewhere up ahead. It is in the striving that we show our greatness. We do not give up. We overcome. And we shall overcome again.

Author: Dr. Brian DeToy

#covid19 #vietnam50 #cambodia50 #kentst50