“We cannot rewrite history, but we can right history.”

~ Judge John C. Hayes III of Rock Hill, SC in 2015

On Jan. 31, 1961, 10 black students sat at a whites-only lunch counter at a local Rock Hill store and asked to be served.

Dragged by police from their stools, the protesters, from nearby Friendship Junior College, were charged with breach of peace and trespassing. Judge Billy D. Hays gave them a choice: pay a $100 fine or spend 30 days on a chain gang.

The choice was clear. They would not pay fines and thereby subsidize a segregationist government. They took the jail time (knowing it would cost the county money for room & board), and thus galvanized the fledgling civil rights movement.

They had embraced a new strategy of resistance: “jail, not bail.” Their idea was to embarrass segregated Southern towns by compounding arrest with the spectacle of being imprisoned merely for ordering lunch or sitting in the wrong part of a bus or theater, or attending an all-white church.

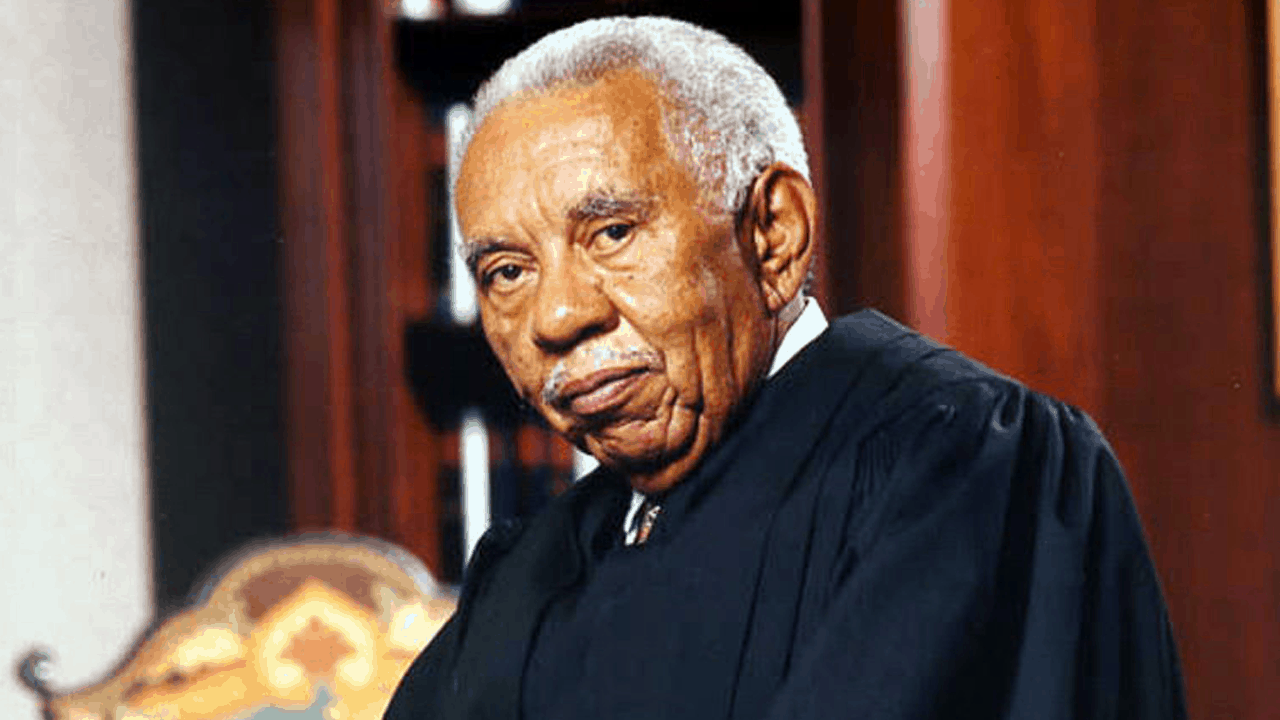

Their lawyer was Ernest A. Finney Jr., who began practicing full time only in 1960 after doubling as a teacher and working part time in a restaurant to make ends meet. He would later represent thousands of other civil rights defendants. Most lost their cases in South Carolina’s local courts. All but two, however, were later absolved on appeal.

54 years after the arrests, Finney returned to Rock Hill to reargue the case. Most of the defendants joined him. Judge Finney, 83, hobbled into the courtroom and rose slowly to address Circuit Court Judge John C. Hayes III.

Wearing a tie emblazoned with the state’s palmetto and crescent moon logo, Finney appealed to the court to exonerate the men, who had been sentenced in 1961 by Judge Hayes’ uncle. “Justice and equity demand that this motion be granted,” Finney declared.

It was. In a bittersweet rebuke to the past, the convictions were overturned. The sentences were vacated. The prosecutor apologized.

Justice Finney graduated from law school in 1954, the same year the United States Supreme Court delivered its Brown v. Board of Education decision. At the time, only a handful of black lawyers were practicing in South Carolina, and blacks were excluded from juries. In 1976, he was elected the state’s first black Circuit Court judge. In 1985, the Legislature named him to the State Supreme Court — the first black since Reconstruction in 1877. In 1994, the General Assembly elected him Chief Justice of South Carolina.

“I would like to be thought of as the man who did the best he could with what he had for as long as I could. All people have a responsibility to be the very best that we can be in whatever we do, and by and large, if you do that, the color of your skin becomes less and less important.”

“For some reason, I have always felt that if America was to live up to its promises to all people, I thought the law would be the basis for change. We knew the law at the time was against us, but we never lost faith that what we perceived to be justice would prevail. When I look at how far we have come today, I have to say, ‘If there’s a man who ought to be impressed with the fact that the law works, I’m that man.’”

Finney died on Sunday in Columbia, SC. He was 86.

God bless Justice Finney and the Civil Rights movement he represented so well.